Without dramatic and immediate changes in the higher education sector, broader economies that support third-tier learning will fail along with it:

People in the community employed by the college will lose their jobs; commercial activity geared toward the student population will fail; and investment in real estate for student housing will no longer have its expected return."

[HOVER TO FLIP]

There can be no doubt now that the student debt problem in America is reaching a breaking point. A relatively well-intentioned system has not been able to keep up with the past three decades of radical economic, technological, legislative, and cultural changes.

Under the current system, teenagers are put in the position of deciding their fate without the tools to plan appropriately, cautiously, and intelligently. Not only is the timing of making huge life decisions inopportune for most first-year college students, but a wide variety of other significant challenges make higher education less attractive and less attainable.

Return on Investment

Until recent history, there was a general consensus that higher education was the doorway to greater financial success in adulthood. The more credentialed and attractive graduates were to employers, the easier they could obtain competitive employment and move up the managerial food chain.

Now that the marketplace has been flooded with more college graduates and the cost of higher education is increasingly inflated, it’s no longer a given that a degree equals greater financial independence and success.

“What we tend to hear is: Yeah, students are taking on a lot of debt but ultimately that debt is worth it because their degrees are paying off in the long run. And we’re finding that that’s not necessarily true” says Julie Margetta Morgan to Vice News. “It’s no longer this thing of, I’d like to earn a higher income, so I guess I’ll go to college. It’s like, I have to go to college in order to not end up in poverty—and I’m also forced to take on debt to get there.”

But why is college so expensive in the first place? For public institutions, cuts to eduational funding have definitely exacerbated the issue of cost. For instance, “In 2003, students paid about 30 percent of the University of Wisconsin system’s total educational cost, according to data compiled by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. By 2013, after several rounds of state budget cuts, students were responsible for about 47 percent, and more state cuts to higher education are expected ( Consumer Reports).”

However, budget cuts are not the only culprit. There are copious services and extra amentities which are aimed at attracting more students to apply and enroll. Additionally, there are significant difficulties that have arisen as the gulf between adjunct and tenured faculty deepens. Rogers and Baum state the issue as:

“College and university budgets rely on inflated real estate investment, deny the short- and long-term effects of student loan defaults, accept the rise in tuition above the rate of inflation as normal, and expect a downsized part-time faculty to help subsidize inflated tenure track and endowed tenure budgetary lines. The insatiable upper administrative appetite for high salaries, job description absurdity, and low accountability adds endless layers of compulsive, prideful incompetence to an already unstable education business model that believes it simply cannot crash.”

Accordingly, it seems that dramatic changes in higher ed budgeting and funding are required to get at the heart of the student loan crisis.

Inequity

There are several qualities which make student loans uniquely unfair as both an obligation and a generational burden. The most obvious is the fact that student loans, unlike credit card or mortgage debt, are almost never expunged via bankruptcy. "Unlike other obligations, such as credit-card balances, [student loans] can’t be discharged in bankruptcy unless it imposes an 'undue hardship.' Courts narrowed that escape route further, in some cases demanding that borrowers demonstrate a 'certainty of hopelessness' — an almost impossible standard to meet. As a result, debtors almost never seek relief” (Bloomberg).

Defaulting on student loans can tank a borrower’s credit score, but continuing to pay high loan bills each month can be crippling for low-income graduates – especially for those who took out loans for school but never finished their degree.

The federal government has repeatedly instituted and amended income-based student loan repayment plans, which can lessen the pressure of having to make exorbitant monthly payments. However, this means that more interest accrues, so the balance can balloon far beyond the original amount. Some of these repayment plans forgive balances after 20 or 25 years of payments, but there’s a downside there as well. “Under current Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules, any loans forgiven under these programs are considered taxable income. In short, this rule means that you could face a hefty tax bill when your loans are forgiven” Melanie Lockert.

The long-term strain even small student loans impose have yet to really float to the surface of the dialogue surrounding this crisis. One of the largest problems borrowers face is the difficulty or total inability to contribute to retirement accounts. Alli Conti states, “The average grad under 35 with debt has around $21,000 in retirement savings. Someone who doesn’t have student loans has an average of almost $40,000…You get socked twice by not being able to contribute to your retirement account when you’re young, one, because you’re just not saving at all, and two, because you’re missing out on a tax benefit.”

In attempting to measure the success of the programs like income-based repayment, the federal government mostly examines the default rates. Margetta Morgan says there is a “subset of policymakers who are looking at the student debt crisis through the lens of repayment—that the goal is to ensure that people can repay their loans. Keeping people out of default shouldn’t be the biggest goal we set for ourselves.”

Economics

Some Americans don't agree that the surge in student loans debt or rising higher education costs signal increasing economic risk. There are politicians and theorists who feel that "the government deserves every penny of interest" accrued by student borrowers (Conti); If one makes the decision to take on student debt, they have a responsibility to pay it back regardless of the outcome of their investment. But a variety of researchers and economists actually argue that allowing the current system to continue will likely result in dire economic consequences for our nation.

The most obvious issue for those with monthly student loan payments is decreased disposable income. The more money that must be spent paying back student loans, the less purchase power borrowers have to participate in commerce. This doesn’t only hit retailers and local businesses, but hits the housing and stock markets as well.

While the global economy has made a slow but steady recovery from the Great Recession, stagnating wages continue to be an issue. This is especially relevant for those who went to school but needed loans to attend. “What [student borrowers] earn each week in terms of purchasing power is less than what their counterparts made twenty years ago” (Sourmaidis).

So what might combat both the diminished purchase power and disposable income of middle- to low-income Americans? Jillian Berman argues, “Wiping away the $1.4 trillion in outstanding loan debt for the 44 million Americans who carry it could boost GDP by between $86 billion and $108 billion per year, on average for the 10 years following the debt cancellation.” This interpretation indicates that struggling borrowers would not be the sole beneficiaries if outstanding student debt was canceled; The rest of the American economy – including the housing and jobs markets – would as well.

“Declining home prices can adversely affect labor market outcomes, and they can impair student loan borrowers’ liquidity by limiting their ability to borrow against home equity” (Mueller).

When looking at the economic impact student loans have on the entire nation, there is a clear indication that the current system funding higher learning is actually feeding a growing financial menace. Higher education should create higher income, but wages are stagnant. When people have less money to spend (both due to low average wages and increased expenses), commerce suffers. And when real estate and the stock markets dip, middle-class Americans have even less purchasing power, especially if businesses and jobs are in jeopardy. It would seem that the path to better wages and job stability is more competitive training and educational credentials, but most must take out loans to get there, thus perpetuating a growing body of an economically challenged middle class. It’s a vicious, self-perpetuating circle.

Given this information, the best resolution to this crisis seems clear. Better repayment plans, decreasing default rates, and trying to slow education price inflation all assist with the problems at hand, but they don’t pull current debtors out of this generational hole.

“As we look to the future, we have to think a lot bigger. We should be looking at both free and debt-free options for college. Free college at public universities and more debt-free options for students. That’s how we take care of generations moving forward. But we also need to do something about borrowers stuck with debt right now. My sense is we should be taking a really hard look at ways to cancel at least some of the existing debt” (Margetta Morgan).

The Bubble

The Great Recession was not an event caused in and of itself by an idiopathic downward spiral. It is inextricably linked to the Housing Market Crash that peaked in 2008. This type of crash perfectly demonstrates what happens when an economic bubble bursts. Investors become enamored of a particular investment, there's a rush of buy-ins without due dililgence, the investment's value falters, and the subsequent dumping of assets causes the "bubble" to burst.

“The higher education bubble (one-sixth of the U.S. economy) will likely burst with the force of all previous catastrophes combined...

—a shock wave so sudden, so large, that it gathers the full force of the savings and loan, insurance, energy, tech, and mortgage crashes, creating a blockbuster-level perfect storm.”

One of the main reasons the housing market fell apart was sub-prime lending, wherein lenders approved and dispersed loans without regard for whether or not the borrower can repay the loan and interest. The mortgage industry was rife with regulatory loopholes, predatory practices, and continually turned a blind eye toward signals that the market was not nearly as stable as everyone thought.

“A basic characteristic of bubbles is the suspension of disbelief by most participants during the ‘bubble phase.’ There is a failure to recognize that regular market participants and other forms of traders are engaged in a speculative exercise, which is not supported by previous valuation techniques. Also, bubbles are usually identified only in retrospect, after the bubble has burst” (Forbes).

When an economic bubble bursts, it makes the value of the investment plummet. Buyers realize that their purchase was essentially a house of cards and race to unload the tumbling asset. Generally speaking, this is the kiss of death for the product, company, or industry involved.

One of the more devastating bubbles to ever burst was the mortgage market crash, which peaked in 2008 and ultimately took the blame for starting The Great Recession. Within a relatively short period of time, not only did scores of borrowers go into default as variable rate mortgage costs soared, but Wall Street came to the sudden realization that the base of their towering financial architecture was essentially worthless. Due to the enormous role the housing market plays in the United States economy, the government stepped in to try to limit some of the damage by giving certain financial institutions financial assistance -what is commonly known as a “bailout.”

Candace Elliott says, “Economic bubbles rely on the greater fool theory. The people who enter the bubble early may not necessarily believe what they’re buying is useful but what they do think is someone in the future will pay them more for it than what they paid themselves. Somewhere out there is a bigger fool, but at some point, there is the last fool.”

And perhaps that exact point – that most bubbles have investors with little-to-no emotional or ethical stake in the product they are trading – is why student loans have grown into the threatening behemoth they are today. A majority of those who have or are considering getting an advanced degree truly believe that education has limitless intrinsic value. There is a cultural awareness that education is good, degrees are important, and therefore cost isn’t as relevant.

However, the inflated price of higher education is finally defining where value and cost diverge. The decades-old adage that “You go to college, you study, don’t worry so much about how much it costs, it’s going to be worth it in the end” has lost its clout, especially among Millennials and Generation Z students who are saddled with a burden previous generations were not.

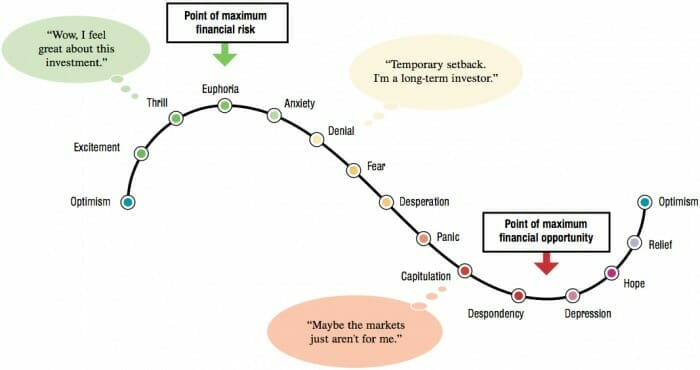

So if the student loan market is truly a bubble, where are we in the predictable cycle? Elliott describes the pattern in this graphic:

If we are to take her at her word, Elliott is sure that educational debt is heading toward a fateful inflection point. “I think the next bubble to burst will be student loans…Lenders started handing out student loans to anyone with a pulse and colleges hiked tuition to obscene amounts.”

Only time will tell whether or not the student loan crisis will morph into yet another large recession, but history seems to indicate that, very simply, we are at the inflection point wherein the value of investing in higher education is no longer worth its cost.

The sad truth is that this issue is not just economic, but has become highly politicized. Easing strain on borrowers, even if it results in financial gain for the nation, is unacceptable to many voters and legislators. No one craves blame, and therefore many are afraid to take a risk by proposing radical change. The bureaucratic bulwark that is the federal government makes change slow and difficult.

But it is easy to forget that there is incredible strength in numbers. When citizens bind together to combat an issue, it becomes far easier to accomplish change. If student loans play a large role in your life or your childrens’ lives, the most helpful thing you can do is to keep the conversation going in your community.

Contact your local and state legislators – they have a huge impact on the price of public school tuition. Don’t rush to take on student debt until you’re really sure what you want to study. And most importantly, stand up for yourself. When it comes to navigating the world of higher education and student loans, you shouldn’t only rely on others to advise you on your educational plan. Do your own research and make informed decisions.

Be your own advocate.